How am I doing as an art student?

I was updating my mom on the phone the other day, and she said she was hoping to see some of my recent work here, so I thought I’d put up a few things from my sketchbooks. Â Later, I’ll take some photos of my life drawings, my first painting project, etc. Â All in all, taking art classes has not led to the production of much art–just a lot of grappling, of various kinds:Â Â

Drawings of hands

Â

Contour drawings of hands

Quick sketches of hands

Contour drawings of objects

Cartoons for comic relief

Escapist doodles

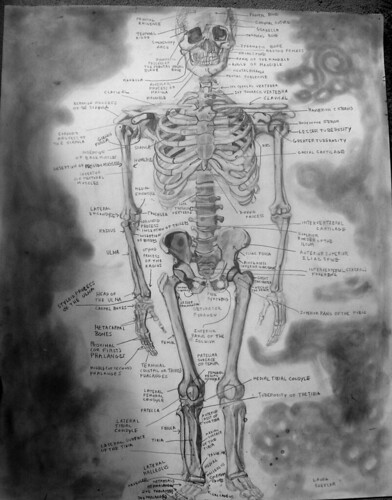

Miscellaneous bones

Response Journal #1

For the art history class I am taking (Modernism 1800-present) I have decided to write a response journal to some of the articles that we read.  This isn’t required, but we did this in my master’s program in Education, and I find that it helps my understanding quite a bit.  As I work toward comprehension, I am doing more summarizing here than response, but I hope that will change as I go along. Â

“The Lost Photographs of Edouard Manet†by Alexi Worth, Art in America, January 2007, Issues & Commentary section, pp. 59-65.The article starts with a quotation from Gerhard Richter in 1964, talking about how “moronic†it seemed to paint from a photograph, around the time he started doing it—because it was something “anyone could do.†In class, the instructor mentioned that painting from photographs or other optical devices was often practice, but kept secret, because it was seen as “cheating.â€

What kind of playing field is it, where such questions even matter? There was a set of standards by which painters’ accomplishments were judged, and I don’t entirely understand them. In the contrasts between Ingres and Manet, Ingres’ distortions of the human body do not raise objections, but Manet’s less refined paint “daubs†provoke outrage But at least the difference is evident in the painting—so why would anyone mind a painting done from photographs if you couldn’t tell the difference? It’s like the painter’s ability to render in paint is not just for the purpose of making an image—it’s also a rite that must not be bypassed.

Of course, I am often inclined to ask, “What’s wrong with art that anyone can do?†and further to argue that really bad art requires special talents. But that’s off topic.The article draws on the research of the art historian Beatrice Farwell to explore the possibility that, while no particular photographs have been tied to Manet, the influence of photography pervades his paintings: “Manet may have transformed painting not by simply appropriating—or resisting—the look of photographs, but by creating…a deliberative, co-optive critique of photographic vision.â€

I like the phrase “co-optive critique†and am trying to think of other examples. Rudy Guiliani in drag is perhaps a co-optive critique of certain feminine fashions. But Worth is talking about co-optation without any hint of parody. Was grunge a co-optive critique of heavy metal? What about contemporary paintings that recast Our Lady of Guadalupe as a contemporary woman? I need to think more about this.

Farwell’s evidence for photographic effects in Manet’s painting is intriguing: Central figures in Olympia, and Le Dejeuner sur L’herb and other paintings receive lighting from the front—a highly unusual strategy at the time, but a familiar sight to “modern eyes, accustomed to the effects of flash photography. Furthermore, The Dead Christ and the Angels is lit upwardly from “a source near the floor,†undoubtedly by some sort of artificial light. Farwell reasons that the early forms of artificial illumination available in the 1860s would have been difficult to use. She judges it unlikely that he could keep the light going safely for long enough to make the painting from life. But he could easily have taken a photograph and painted from that.

Farwell wrote these observations up in her 1973 dissertation, which was published in 1981, but her colleagues showed little interest, preferring to see Manet as an artist who remained independent of technology.

I am only beginning to understand more about how art historians decide which topics are worth pursuing and what the standards of evidence are. Where facts lie undiscovered or may be unrecoverable, Worth weighs the likeliness of one hypothetical account over another and claims Farwell’s arguments not as truth but as indicators of research areas that could prove fruitful.

Both Farwell and Worth, believe that a further investigation into Manet’s relationship with photography might provide a richer understanding of the painter’s impact on modern art. While Manet incorporated photographic lighting styles, Worth proposes that his “sketchy†painting style may have been a reaction against the crisp verisimilitude of the daguerrotype, with Manet defending, instead, the less-literal representations of Old Master paintings: “Our very failure to recognize Manet’s photographicity is, in part, a measure of success.†I will think about this article as I learn more about rejections and resumptions of photorealistic ideals.