The other night, Raymond and I were sitting around in our “living room,†which consists of our beloved plush brown sofa that we shipped from Pittsburgh to the West Coast, plus a few square feet of surrounding floor space. We’ve each got a folding tray table, supposedly for eating on, but instead we have piled them with our respective messes. We take our meals from plates that we hold in our laps.

Raymond’s pile consists mostly of reading matter. His library books cover topics like social justice, Bach, and how to rebuild civilization in the wake of catastrophic events. Typically, it’s just one of these topics per book, but sometimes there’s an overlap. Resting askew on open copies of the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, mingled with an e-reader, a t-shirt, or a moleskine or two, these look ready to slide into a catastrophe of their own, although they never actually fall.

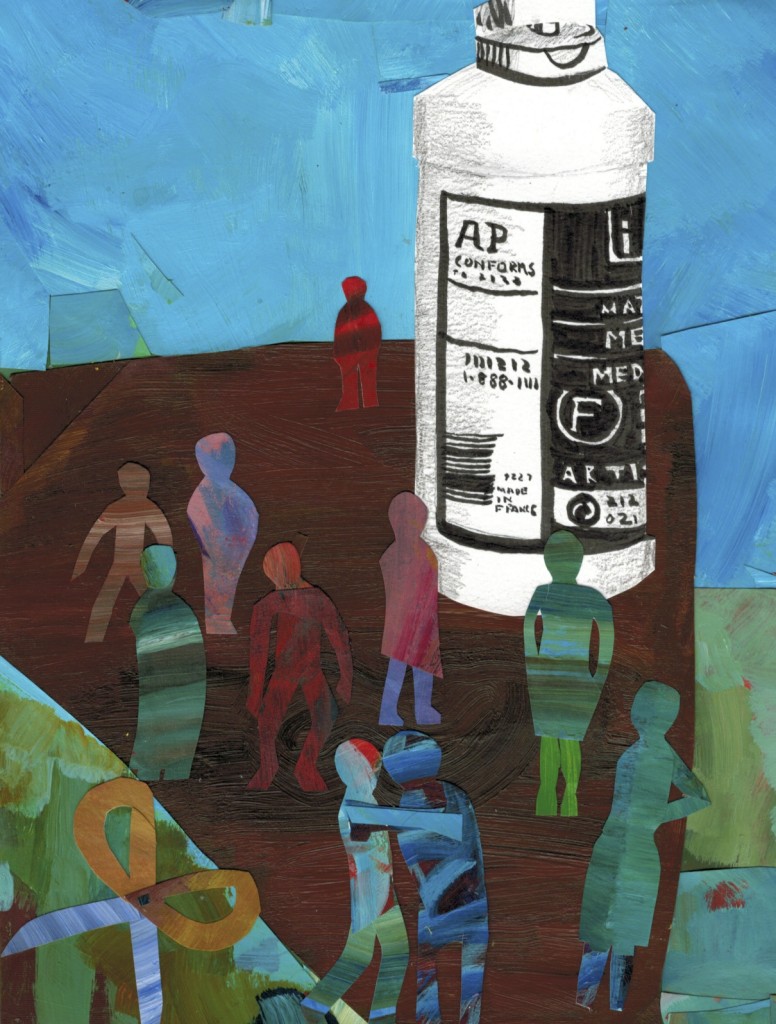

My mess consists of polymer and pulp: clear boxes of paper scraps, smeared and scratched and dotted with acrylic paint. Brightly painted paper scraps stuffed into envelopes and freezer bags.

The more enterprising paper scraps liberate themselves from their boxes and bags. I corral them back from the floor and the sofa cushions but never seem to get the table entirely clear. They congregate around the bottle of liquid matte medium, the perfect glue to compensate for my lack of patience and precision. Unlike the glossy stuff, which crisps up into shards, the matte medium can get all over your fingers and will just peel off when it dries. Other landmarks include pens, scissors, and black trays that used to hold frozen chicken tikka masala. The world’s smallest art studio, my little folding table bustles like a village.

So when Raymond and I sit on the sofa, we are often in several places at once, shipping off through various methods of cultural transport. Raymond picks up the New York Review, and he’s outside the walls of Troy with Mary Beard. I can’t tell you how many times we’ve been to the White House with Olivia Pope—and if you’re reading this in 2014, it’s possible that the same is true for you.

On the night in question, however, having caught up with all available episodes of Scandal and anything else worth watching, having even zip-lined over a tropical forest and dangled a few perps out the window on Hawaii 5-0, we were listening to a podcast.

Heckling a podcast, to be exact. The author David Gilbert was reading Steven Polansky’s short story “Leg,†in which a father, helplessly alienated from his wife and son, refuses treatment for his injured and eventually festering limb. As Dad tried to “cauterized†his wound with a scalding-hot towel, we shouted our objections, to no avail. (Olivia never listens to us, either.)

After a few days, he’s unable to walk, and his distracted wife gets around to asking, half-heartedly, whether he might want to go to the doctor. At this point, the crowd—that is, Raymond and I—went wild. We gave up trying to straighten out the characters and started hollering at each other. If your leg ever starts stinking and oozing, nobody around here is going to be asking. Your ass will be at the doctor’s. That’s me with the bad language. “Emergency room,†said Raymond. “Get him to the emergency room.â€

And it’s only as I write these words that I realize that this essay is about more than sitting around on the couch. Though there’s been no literal festering, we’ve encountered loved ones who shied from—or bristled at—support that they needed. Unlike the characters in the story, we are blessed with family and friends who are warm, attentive, even vigilant about one another’s well being. Still, we sometimes feel a need to reaffirm our interdependence.

Rolling around on the sofa, howling and laughing, clutching our own uninjured legs, we are also extracting promises from each other. Offering them, too:

I promise not to break your heart with worry. If I need care, I will submit. If you’re the one in trouble, I won’t get distracted. I won’t let you go to ruin. My table may be messy, but you’re a different story.