Here are some of my post-Trump writings, brought over from facebook:

November 9, 2016

Where to even start? I’ve experienced grief and intense worry, but never before in this combination so deeply rooted in my body. I passed a woman who was walking down University Avenue full-out weeping. I talked to a middle school student who is bemused by the (over?)reactions of her classmates, who feel that the world is ending. How can I be reassuring here and still authentic? She’s telling jokes to lighten the situation, and I can’t laugh with her. What I did was define some specific worries of mine while letting her know that I do believe she will be all right.

I remember Reagan’s election and the starts of all our recent wars as times when it felt to me like the world was ending–and it didn’t, but the costs of those have been weighty and lasting.

Still, I’ve been enormously heartened by the energy and enthusiasm that I’ve seen in the past few days from volunteers and among my friends: The pair of teenage sisters who showed up to phone bank, holding hands for courage; the father searching for a Hillary button for his young daughter, she of the hand scooter and pink helmet; those of you who made sure that your children understood your passion for this country, as expressed through your vote.

A bit weepy myself this morning, I was at Yali’s Cafe choking up over the eponymous Yali as he rang up customers, pulled espressos, and chatted up patrons with philosophical shrugs and charismatic smiles. I’ve been watching him do this on and off for–what?–fifteen years now? Slinging his tall, agile self around the cafe, turning his chair around backwards to sit on, leaning his elbow on a table to listen an applicant for barista. Radiating warmth and extroversion and supreme entrepreneurial joy.

Only now he’s not so agile. Earlier this year (or late 2015?) he was in a catastrophic car accident in Israel, where he spent months recovering, his body too broken to travel. Then he was back at the cafe, but sitting at a table with his hands folded in front of him. Later he started moving around the place, slowly, tentatively. Today, he had regain most, though not all of his dynamism. He’s got a kink in his neck that bends his head forward, and that called my attention to a new dusting of gray in his black curls. He’s bulked up, though. Must be lifting weights.

I was there this morning because last night a blast of reality froze my brain and I left my laptop at a students’ house. (His older brother happened to be on campus and met me there to give the computer back to me) It good to be in a familiar public environment Yali was steaming milk and I was scanning his solemn face for that old radiance, and then he turned to someone and the light went on, more slowly but maybe also more brightly than before.

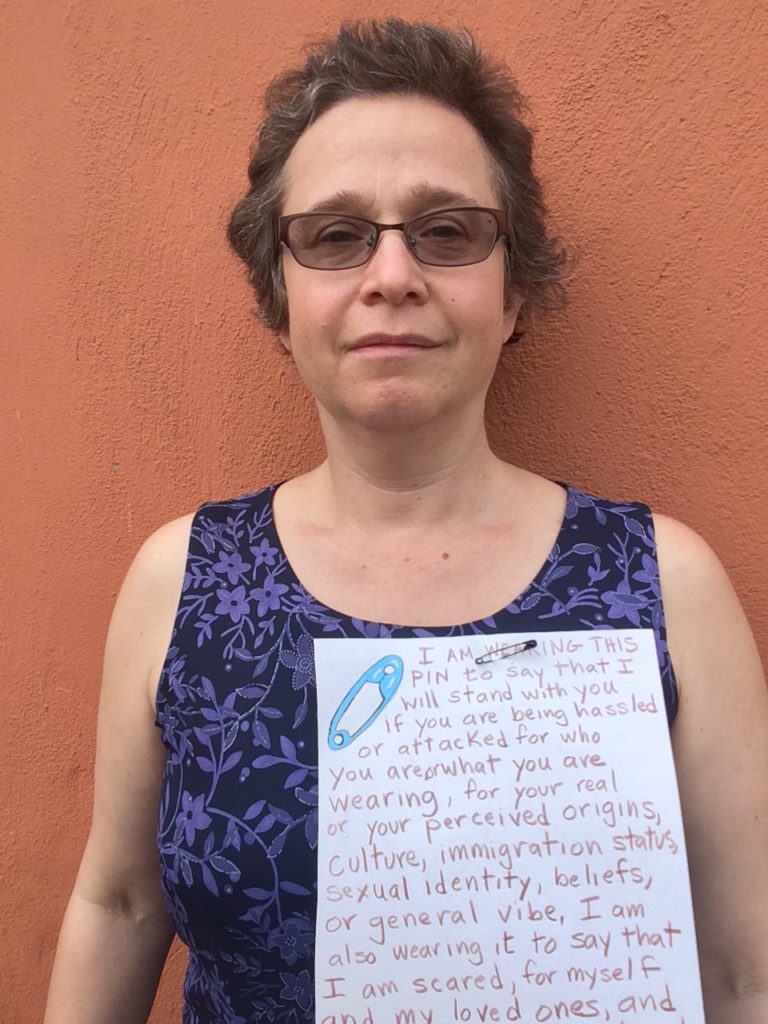

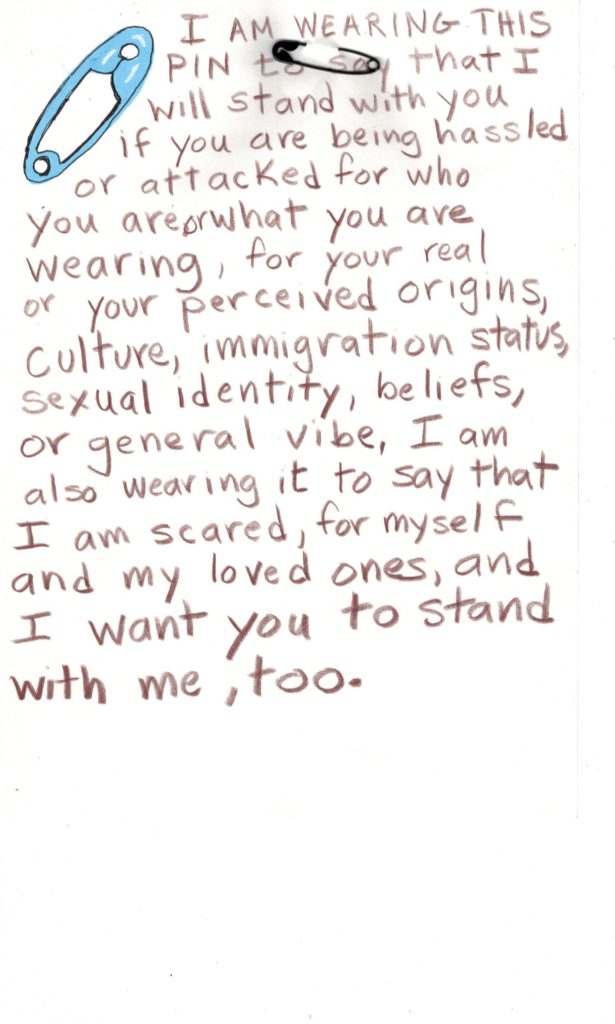

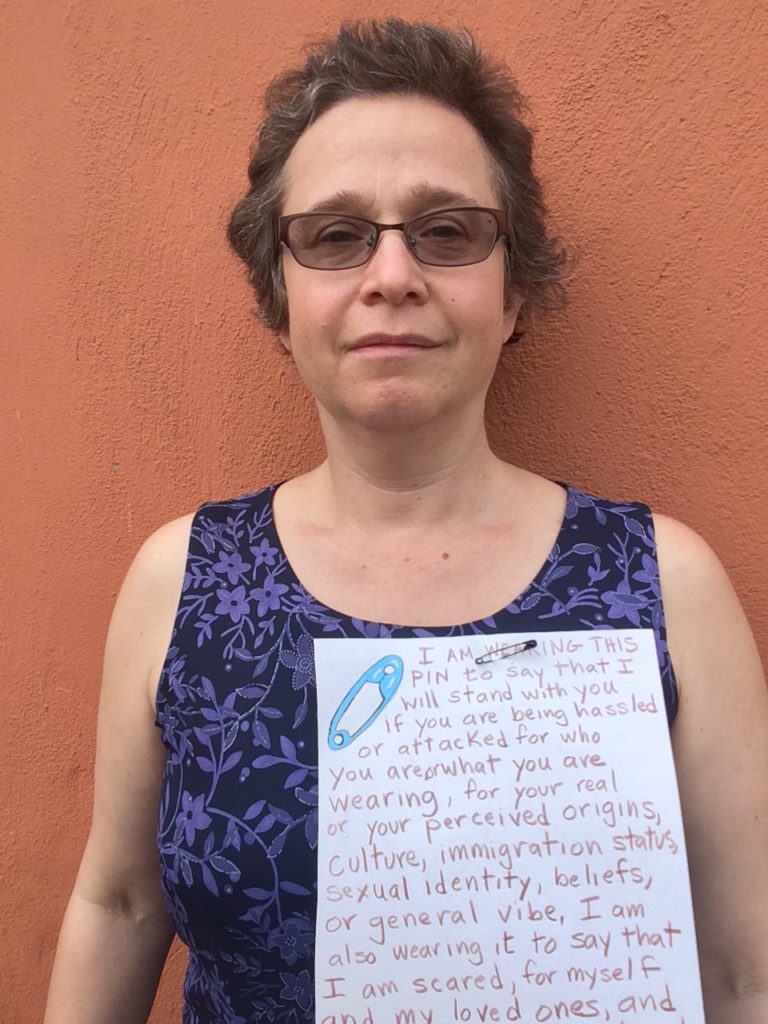

November 11, 2016

So, my first day wearing this sign, not much happened at first. It felt like people were going out of there way to avoid looking at me, although a few middle-aged women gave me warm smiles. Then Raymond and I ran into some people he knows from his church, people I had never met before. The woman read my sign from start to finish, then hugged me and read it out loud for her husband. (They were on their way to to Peet’s with a VA document in hand to get a free coffee for him.)

At the YMCA in downtown Berkeley, a blond woman called out to me and asked to read the sign, then nodded soberly and said, “Thank you.” She talked about how nervous she has been and how worried for friends of hers who are people of color and suffering deeply.

We went swimming, and afterward in the locker room, there was a mother and daughter who I thought might come from the Horn of Africa. The girl screwed up her face looking at my sign, so I stood up straight for her to read. She worked her way through the whole thing slowly, then, finally, smiled. The mother came over to see what was going on. She read the sign too, then said, “That’s nice! Thank you.” The girl said, “I like your drawing of the safety pin.”

I think I’m going to try wearing the sign for a week, then falling back to just the pin. I’ll keep writing about what happens.

November 12, 2016

Working on a personal manifesto for activism in this era. Here’s where I’m starting.

I want to be disciplined in my political speech. Model the kind of civil discourse we would like from our opposition. Boycott mockery and exaggeration. Fact-check rigorously. Expect the same from any source that I re-post. Ask the same of friends.

Some people may not be able right now to do what I am calling for here. Or may make different choices about how to express themselves. This is on the right or the left. I’m going to try not to referee or police or say “people need to…†I *am* going to *ask* people to reconsider.

I am going to fight every day to resist the normalization of Trumpism. The only way that I can do this is by taking personal risks in my “zone of proximal development.†In education, the ZPD is the sweet spot, the goldilocks zone for learning, neither too easy, nor too difficult. This week, it’s wearing a sign that expresses my emotions and invites strangers to interact with me and share their feelings about the state of society.

Fighting the normalization of Trumpism cannot mean going back to the status quo pre-Trump. We deserve a lot better.

Comment: Note about asking people to reconsider their political speech: I want to be mindful about what I ask and when. Asking things of people is a privilege that needs to be earned.